Recently, I’ve read some discussions about the inappropriate depiction (in art or speech) of the kami in Shinto. Westerners tend to want to have a very close, friendly connection to Shinto kami, but this is rather odd–borderline disrespectful–from a Japanese point of view. I read an article in the Jinja Shinpou (3 June 2019) about this, so I thought I would translate it here for you.

Recently, I’ve read some discussions about the inappropriate depiction (in art or speech) of the kami in Shinto. Westerners tend to want to have a very close, friendly connection to Shinto kami, but this is rather odd–borderline disrespectful–from a Japanese point of view. I read an article in the Jinja Shinpou (3 June 2019) about this, so I thought I would translate it here for you.

Fearful Respect

by Suzue (Vocalist, and a shrine ritualist at Kono Hachimangu

When did it start, I wonder. Recently I can’t help but feel that the word “kami” has started to be used all over the place. You probably aren’t familiar with these expressions, but “kami response”, “soon a kami!”, “kami level”, “to kami (something)”, “k4m1” are all phrases used to supposedly express the highest praise. However, something about them feels a bit cheap to me. The last phrase “k4m1” (ネ申す), by the way, uses net language to express the character “kami” (神) written side-wise, thus emphasising the meaning.

Thinking charitably, this is not the worst trend in the world. I want to consider this positive as a felt everyday connection to the kami as expressed in our contemporary language. But, including the feeling expressed in these phrases, I wonder if we modern people haven’t unconsciously started losing our sense of respect for those above us, started becoming slightly arrogant.

Fearful Respect. Is this not an innately human feeling? When faced with a deserving object, this sense of respect naturally bubbles up from within ourselves. Kami (神) is pronounced the same way as up (上, also read “kami”). When we focus on an existence higher than ourselves, it also clearly raises our own selves up. By understanding the self we have yet to accomplish, we enter into a position to learn.

The feeling of fearful respect is not something we learn from a teacher. It comes naturally from within: a sense of the awe-ful fostered within our hearts. Since I was raised at a shrine, perhaps I may have been able to naturally experience this feeling more easily. When my father placed his hands together before the shrine… when my mother offered her carefully steamed rice before the kamidana… when sunlight gently bathed me while I was lost in through by the window… every time when I gazed up at the trees of the shrine forest: These everyday things taught me a sense of fearful respect.

This is just my personal experience, but when I was in intermediate school, I had a chance to talk to an American, who was a Christian. He nonchalantly said, “God (kami-sama) is my friend.” I was really struck by this pronouncement. I felt it was quite novel, but at the same time it felt quite presumptuous. I was also surprised when I was in high school and one of my classmates said, “My mama and I get along so well, it is like we are best friends!”. I had never once felt like my mother was my best friend, and just couldn’t imagine it.

Also, a friend of mine who is a catholic priest told me this: “God (kami-sama) exists up in Heaven so high above us that we cannot reach Him. Thus it was for that reason that he sent Jesus down to this world for us.”

I imagine that people vary in the distance they feel to the kami. Near or far, only you yourself can truly know.

“I fearfully intrude…” (NB: a polite way of saying “excuse me” in Japanese). I love this phrase. I feel like people in Japan originally approached another person by pulling back a step, keeping a feeling of slight distance.

Faith is not an expression of rank or height. But actions like looking up or bowing down your head express a 3D sense along a vertical axis. A feeling of equality with everyone on the same step is also important, but I want to remember the importance of humility and respect too.

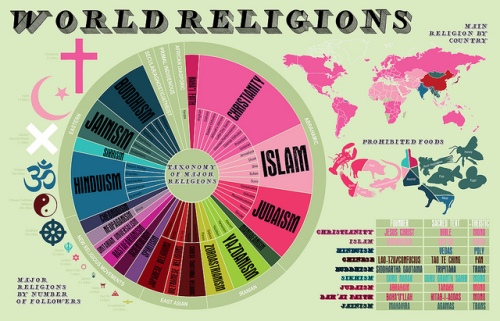

This “world religions” infographic is so interesting because it clearly demonstrates the Western-centricity of our modern taxonomy of “religion”. First we have the large pie chart on the left. It’s outer circle gives a rather disparate group of large categories. Most of these are vague geographic categories (East Asian, Eastern, African Diasporic, Iranian), but “Abrahamic” gets its own category. This implies “Abrahamic” is a category of the same level as “East Asian”. However, “European” or “Germanic” etc. would be more appropriate category. Thus Abrahamic religions are united into one category while that same unity is denied other parts of the world. Furthermore, the very diverse indigenous traditions from (non-literate) peoples across the globe all get lumped into the single category of “Primal Indigenous”.

This “world religions” infographic is so interesting because it clearly demonstrates the Western-centricity of our modern taxonomy of “religion”. First we have the large pie chart on the left. It’s outer circle gives a rather disparate group of large categories. Most of these are vague geographic categories (East Asian, Eastern, African Diasporic, Iranian), but “Abrahamic” gets its own category. This implies “Abrahamic” is a category of the same level as “East Asian”. However, “European” or “Germanic” etc. would be more appropriate category. Thus Abrahamic religions are united into one category while that same unity is denied other parts of the world. Furthermore, the very diverse indigenous traditions from (non-literate) peoples across the globe all get lumped into the single category of “Primal Indigenous”.